When the Small Business Investment Act of 1958 passed through Congress, it signaled a Sea-change in how entrepreneurs could raise and receive capital. It effectively fired the starting gun for what is now known as Venture Capital (VC) in the United States.

In the 50 years that followed, corporations increasingly looked for Venture Capital to inject necessary funds and scale their operations.

Despite its long history, the process of raising capital has remained an expensive, time-intensive, and often deadly (for the business) undertaking. Anyone who has been involved will know that the process – from the initial meeting to the signed term sheet, to finally receiving the money – can take anywhere from 3-18 months. That’s far too long for most startups.

Not only that but founders are typically forced to give up 20-25% of the business in return for an early stage investment. If the business manages to scale its operations, the sold equity would be worth millions. As a result, the founders often give up ten times more than they initially receive.

Most importantly, early-stage Venture Capital changes the direction of the business from creating a great product to achieving astonishing levels of growth. This misalignment stems from the fact that early stage investors seek the appreciation of the company’s value above all else. In order for the investors to make money, the startup needs to raise additional rounds of funding at a much higher valuation – finally going public through an Initial Public Offering.

It’s no wonder then, that alternative forms of fundraising have begun to thrive. With the emergence of Bitcoin in 2009 and Ethereum six years later, the blockchain space has positioned itself at the frontier of this revolution.

In 2018, the funds raised through token offerings surpassed Seed and Angel Investment for the first time in history. Given the problems outlined above, it’s easy to understand why.

Let’s now look at the two most popular forms of token offering and compare them.

Security Token Offerings (STOs) vs Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs)

| STO | ICO | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of token | Security token | Utility token |

| Amount raised (USD) | $300+ million | $22.5+ billion |

| Most raised | Spin ($125 million) | EOS ($4.2 billion) |

| Participants are | Investors | Users |

| Token holders want to | Make a profit | Participate in service |

| Treated as a security by the SEC | Yes | No |

| Open to retail investors from the US | No | Yes (although often excluded) |

| Open to accredited investors from the US | Yes | Yes |

| Typically needs an approved Prospectus | Yes | No |

| Typical token structure | Tokenized equity, tokenized debt, equity share | Voting, payments, staking, various forms of platform participation, etc. |

| Liquidity | Poor | Good |

What is a token offering?

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, it’s worth taking a step back to explain the concept of a token offering.

In its simplest form, a token offering involves a platform which creates, sells, and issues digital tokens to individuals and institutions. From a business perspective, the purpose is always to raise funds in order to accelerate development and growth.

The motives of the individual are often harder to decipher. When Ethereum launched its ICO in 2014 for example, the atmosphere was that of a Kickstarter project. Ethereum introduced an array of novel solutions and clearly had a huge amount of potential to advance the blockchain industry as a whole. Crypto enthusiasts were more than happy to support it.

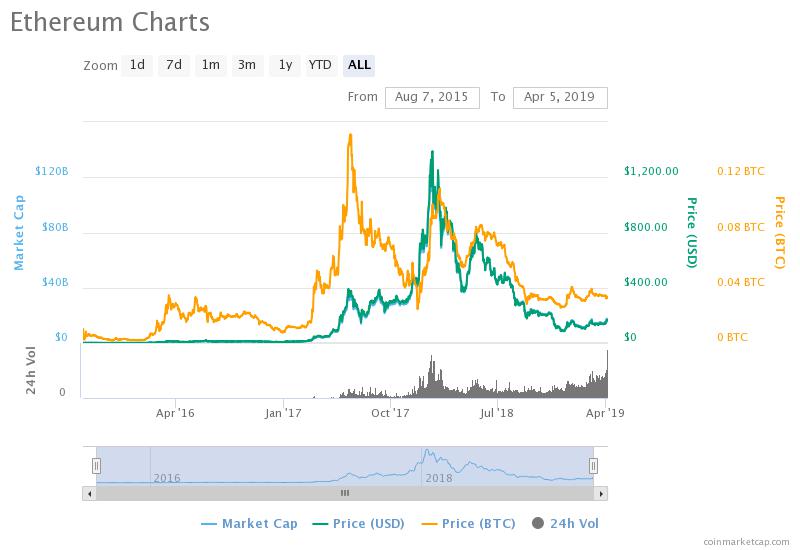

What happened next was an almost unprecedented success story. The ETH token, sold for $0.31 at the time of the ICO, exploded in value – almost reaching $1,400 by the end of 2017.

Image source: CoinMarketCap

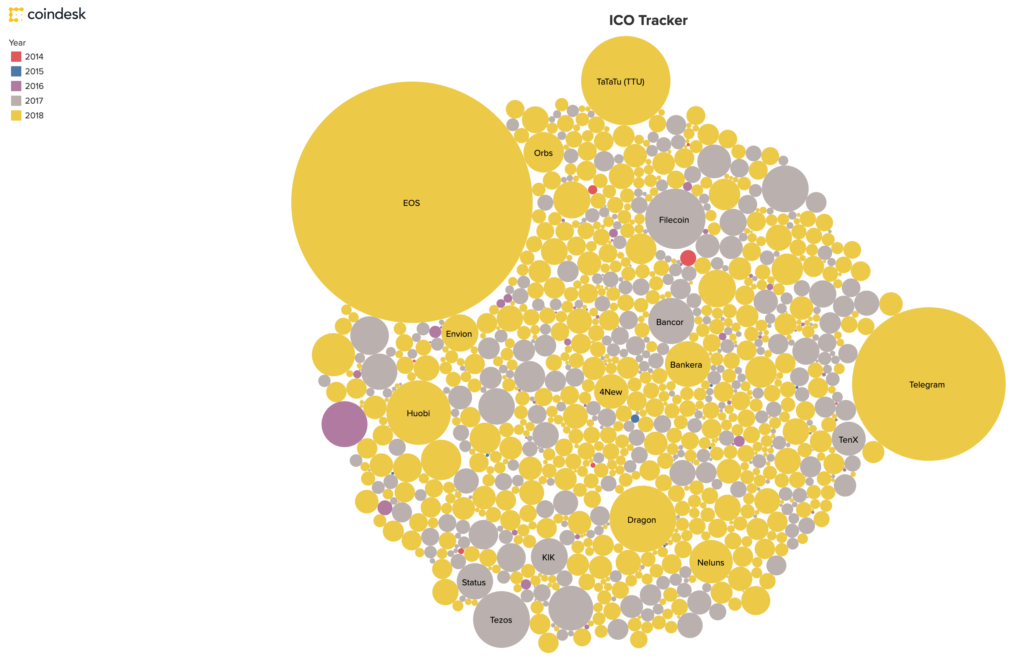

Unsurprisingly, both investors and startups saw this as a huge opportunity to make some easy money and the number of Initial Coin Offerings went through the roof.

Image source: CoinDesk

Unfortunately, easy money dries up quickly and the vast majority of projects have either failed to deliver a product or shut up shop. According to Finance Magnates, 86% of tokens issued through an ICO are now worth less than they were at the time of the sale.

In a nutshell, this is why regulatory bodies like the SEC (US), BaFin (Germany), and Finma (Switzerland) have gotten involved.

Regulation is the key difference between ICOs and STOs

As outlined above, both Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) and Security Token Offerings (STOs) aim to raise funds through the sale of a digital token.

The most important difference between the two is that STOs fall under the purview of regional securities law, whereas ICOs do not. An STO sells a security token; an ICO sells a utility token. The practical implications vary by country.

In the US, it means that an STO is only open to accredited (also known as professional) investors. The reason for this is that securities are deemed very risky by the SEC and the exclusion of retail (or non-professional) investors is designed to protect them from severe financial loss.

Ring any bells?

In Germany and Switzerland, for example, an STO can serve all investors as long as it has an approved Prospectus.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on the United States, but it’s worth taking some time to read up on regional differences – especially if you’re considering launching or participating in an STO.

That being said, regional differences apply to the US as well. This is because a Blue Sky Law ostensibly gives states the power to regulate the sale of securities within their borders.

Nevertheless, the key to understanding securities in the United States is the Howey Test. This is essentially one question which is: do investors buy the token because they expect financial profit solely from the efforts of the issuer?

The Howey Test is painfully vague. How can an issuer know the motivations of the investors? What happens if the token price increases in value? Can a utility token become a security token over time?

The function of the token is a key difference

According to the Howey Test, the primary function of a security is to generate profit. For the cryptocurrency world, this is an unacceptable definition because digital tokens have been freely tradeable and consequently fluctuate in value. Although the Howey Test may work for a government bond, for example, it is far too limited for a digital token with many properties and functions.

Nevertheless, the SEC has begun a slew of investigations which are reclassifying past ICOs as STOs. The two most prominent examples of this are Airfox and Paragon, both of which sold utility tokens in 2017 and have now been penalized by the SEC for selling securities.

If you are planning on launching a token offering it is, therefore, crucial to be clear on the function of the token. Importantly, the SEC’s statement on ICOs reads:

“ICOs, or more specifically tokens, can be called a variety of names, but merely calling a token a “utility” token or structuring it to provide some utility does not prevent the token from being a security.”

Due to this exceedingly liberal approach, many ICOs are now actively excluding all US investors (even accredited) simply to avoid the risk of an SEC penalty further down the road. In the case of Airfox and Paragon, both platforms were forced to return all the raised funds as well as paying a $250,000 fee. Ouch.

Part of the problem is that utility tokens provide a myriad of functions and are not easily categorized. Augur’s REP token, for example, has a completely different function than SelfKey’s KEY token. In general, it’s accurate to say that utility tokens provide access to a service, but this is too broad in the eyes of the SEC and a more specific definition is still required.

To avoid this regulatory morass many platforms are looking to Security Token Offerings to raise capital. The big downside with STOs, is that US retail investors are excluded and only accredited investors may participate.

Only US Accredited Investors may participate in an STO

In order to protect people like you and me from high-risk investments, the SEC excludes retail investors from Security Token Offerings. Instead only accredited investors are permitted.

In the US, the SEC uses the term to refer to individuals who are financially sophisticated and wealthy enough to make informed decisions about investment opportunities. In order to qualify you need to meet certain requirements. An accredited investor must:

- Earn over $200,000 per year or havenet worthrth of more than $1 million or

- Have made over $300,000 annually together with a spouse over the preceding two years or

- Be an entity with assets exceeding $5 million.

Importantly, token offerings must explicitly ask and check if an investor is accredited. It is not enough to include a check-box for example. Instead, they typically use specialised service providers during the Know Your Customer (KYC) onboarding flow to verify income, net-worth and assets under management.

What are the KYC requirements of ICOs and STOs?

The increased regulatory requirements for STOs also include more rigorous Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) requirements. This is important both for the investor as well as the platform.

When ICOs first became popular it was often enough to simply enter your email and wallet address. Now platforms typically ask for much more information and often require proof, such as a proof of residence (utility bill for example).

As of April 2019, there is no standardized KYC procedure for ICOs, meaning your experience will vary depending on the legal advice given to the platform you are signing up with. In the case of STOs, the process is predictable. Typically an investor needs to provide:

- Email address

- Phone number

- Full name

- Date of birth

- Current address

- Proof of address

- Employment status

- Annual income

- Accredited investor check

- Reason for investing

For small to medium-sized businesses, collecting and maintaining this information is costly. As a result, platforms like Polymath, tZero and Securitize have sprung up with the aim of providing the infrastructure required for a compliant STO.

How does the secondary market differ?

The secondary market is another key difference between ICOs and STOs. In the case of an ICO, the tokens are freely tradeable on exchanges like Coinbase, Binance, and Kraken. It makes no difference if you trade BTC with someone from Germany or Australia for example.

For security tokens, the secondary market is far more regulated. In the US, the JOBS Act of 2012 clearly defines how securities may be traded. Unfortunately, this includes a one year restriction on trading in the secondary market. As a result, STOs typically suffer from a lack of liquidity with investors unsure of how to sell their tokens should the need arise.

This is particularly painful because one of the great advantages of a security token is the power to make illiquid assets liquid. Property, bonds and company shares are just a few instances where a strong secondary market would represent a huge step forward.

Conclusion

In the introduction, we outlined the significant disadvantages of traditional fundraising methods and discussed the advantages that token offerings initially brought to the table. After crypto’s summer of love, increasing scrutiny from the SEC has effectively extinguished much of the early promise.

Instead, ICOs are often excluding US citizens out of fear of retroactive penalties. For STOs the regulatory situation may be clear, the infrastructure is still weak and the limitations are significant. In effect, launching an STO has become expensive, time-intensive and often deadly – exactly what it aimed to replace.

Title IV Regulation A+ of the JOBS Act may offer a small glimmer of hope, it still seems like the party is well and truly over for small to medium sized businesses.

Leave a Reply